The following interview with Howard Cruse was conducted by PopImage editor Scott J Grunewald and was originally published at PopImage on February 15th, 2006. It appears here with the kind permission of Mr Grunewald. Gay League thanks Mr Grunewald and Ed Mathews for his assistance in facilitating the arrangement.

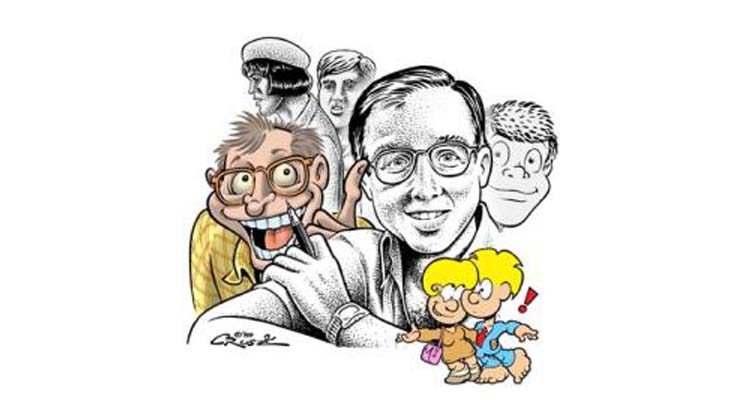

Howard Cruse is a legend in independent comic art, specifically underground gay comix. A son of the south and a preacher man, Cruse was born, raised, and educated in Birmingham, Alabama. Cartooning has long been a part of his life

In the 1970s he drew a daily newspaper comic strip, served as art director and improvisational puppeteer for a Birmingham television station, and did paste-ups for a Birmingham ad agency while cultivating a national following in underground comic books. Moving to New York in 1977, Cruse art directed Starlog magazine until a fulltime cartooning career became practical in 1978.

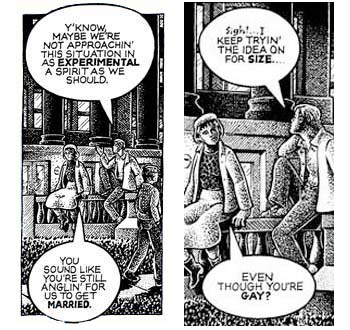

In 1983 Cruse introduced his comic strip Wendel to the pages of The Advocate, the national gay newsmagazine, where it appeared regularly until 1989. He was also the founding editor of GAY COMIX, an underground comic book series created as a forum for LGBT cartoonists who wished to draw authentic comic strips and stories about their lives.

Cruse’s critically acclaimed graphic novel STUCK RUBBER BABY was published in 1995 by Paradox Press, a division of DC Comics, and has since appeared in German, Italian, and French editions, with a Spanish version currently in the works. Spanish translations of his collected Wendel strips have been published in two volumes by Ediciones La Cupula during 2005-06.

For over 25 years, Cruse has been entertaining comic fans. He continues to do so to this day. In 2005, PopImage secretly commissioned Cruse to do the final comic story arc of the daily gay romance anthology, Young Bottoms In Love, which is finally being published this week.

Cruse and his partner Ed Sedarbaum moved to the Berkshires in 2003 after sharing twenty-four years as a couple in New York City. They were married in July of 2004.

Since PopImage is on the web I think it’s only appropriate to start off by talking about your web comic Barefootz. The idea of an artist updating past work is a controversial one and yet you seemed to really like the idea of updating your Barefootz strips for a web audience. Did it have more to do with making older and rarely seen comics accessible to younger readers who had never had the opportunity to see them or was it maybe about you looking back at older work and enjoying the idea of ‘fixing’ or ‘improving’ it?

It all started at a Book Expo in New York when I ran into Tom Hart, who was preparing at the time to be the editor and a contributor to Serializer.net, a projected “sister site” to Joey Manley’s Modern Tales webcomics site. Tom and I both taught cartooning at the School of Visual Arts in those days but we hadn’t spent that much time socializing away from the school.

Tom suggested that I think about creating a webcomic for Serializer. I was intrigued by the idea because I had enjoyed the way my comics looked onscreen on my own site. The comics at Howard Cruse Central had almost all been adaptations of old work rather than newly created work, though. I quizzed Tom about whether there was any way that drawing comics for the web could produce enough income to cover the time it takes to do the writing and drawing. That has always been the catch when I have thought about doing new stuff for online display. I still had a lot of lingering debt left over from STUCK RUBBER BABY and other stuff, and my income from freelance work was just not healthy enough to subsidize projects done just for the fun of it. It wasn’t then and it still isn’t. Unfortunately, even though SOME income is generated by comics created on subscription sites like the ones Joey was building, Tom had to admit that, short of a runaway hit, it wasn’t likely that anything I might do for Serializer would pay for itself.

Still, I was intrigued by the idea of venturing into this new medium on an experimental basis, and a few days later I began thinking about all the Barefootz strips from the 1970s that I still thought were funny but that had never been anthologized. They would have been included in a companion compilation to EARLY BAREFOOTZ, which Fantagraphics published in 1991, but EARLY BAREFOOTZ was such a commercial flop that all ideas of a second compilation covering 1984-89 were swiftly abandoned. Barefootz has always been an acquired taste that a majority of comic’s readers never acquired! You can take a look at my online feature Through the Swinging Seventies with Barefootz to get a feel for its iffy status among underground comix readers.

Being the stubborn airhead that I am, however, I continued to believe that a bunch of those old Barefootz strips were funny and that it was a shame that they had stayed unavailable for decades. So I thought about turning the ones that still held up into a new feature for Serializer. They would need to be redrawn because they were all black and white and were drawn during a period when I had used Zipatone screen a lot. Scanners really hate Zipatone, and it would have been more work to eliminate the screen from the old strips in order to add color than to draw them again from scratch. And I liked the idea of re-drawing them anyway, since I feel that I draw in a looser, more spontaneous way now than I did when I was starting out.

In theory it would not be as much of a burden to do this short-term revival of Barefootz than it would have been to write new scripts on top of drawing new drawings. The writing of a comic is the hardest part; it can eat up a huge amount of time and leave you much more vulnerable to getting blocked. So I proposed the idea to Tom and Joey and they went for it. It helped that I had a really deft summer intern, Tintin Pantoja, helping me with colouring and some of the other nuts-&-bolts preparatory stuff that summer. It’s the only time in my career that I’ve had any kind of assistant, and boy, did Tintin make a difference!

What were some of the responses to the new material? Did old readers feel differently about the new incarnation than new readers?

Everyone pretty much ignored the series while it was playing at Serializer, with the exception of Joey Manley himself (who harbored a soft spot for some of the long-forgotten strips I dug up) and Tom Hart, who was as supportive an editor as anyone could ask for. Barefootz has always been an acquired taste, and my current thinking is that it’s a taste the masses will finally begin acquiring sometime around the mid-22nd Century! Now that I’ve transplanted the series from Serializer.net into my own web site and reworked it a little with Flash, I get occasional laudatory emails from people who discover it by accident and have fun with it. That’s fun.

Did working on Barefootz: The Web Incarnation and now the final installment of Young Bottoms In Love remind you of producing WENDEL on a regular basis?

Barefootz was a special case because, as I said, I didn’t have to write it. Well, I threw in a few new episodes for the hell of it, but for the most part all the writing was done before I started. The YBIL story is newly written, but it’s a short-term commitment. WENDEL was a whole different animal. It was the center of my creative life from 1983-85 and then again from 1986-89. I lived and breathed it. Because it was a serial being created as it went along, the writing demands were constant. I could do it because The Advocate was willing to pay me enough to make it essentially a full-time job. Not many publications are willing to shell out serious money for a comic strip. Even The Advocate seems to have lost its interest in publishing comics, although they do have a comics-friendly Arts Editor who writes about them from time to time.

Did you approach The Advocate about publishing WENDEL, or did they seek you out?

They wrote and asked to reprint my 1981 strip “Sometimes I Get So Mad” shortly after it appeared in the Village Voice. That’s basically how we connected with each other. I don’t think they even remembered that I had done a few gag cartoons for them years before that, while I was still living in Alabama.

Anyway, “Sometimes I Get So Mad” looked so good in the big, roomy page format The Advocate used back then that my appetite was whetted for more showcases like that.

Later on, when I finished drawing “Dirty Old Lovers”, a 5-page story that ran in the third issue of GAY COMIX, I decided that Luke and Clark had a lot more life left in them and I suggested to Robert McQueen, The Advocate’s editor that I cook up a mini-series about these guys. I’ve rarely had characters who were more fun to write dialogue for than Luke and Clark! They would start bantering inside my head and all I had to do was transcribe! McQueen liked the idea of a comic strip created exclusively for The Advocate but he preferred that I create a new central character who was younger and cuter. I hated to give up on the idea of a “Dirty Old Lovers” series, but once I got a feel for Wendel Trupstock I became enthusiastic about exploring his life.

A few years later, of course, I snuck Luke and Clark into WENDEL after all. (It turns out that Clark is Wendel’s uncle, what a small world!) So they made it into The Advocate in the long run where I could have fun with them again.

One of the things I remember quite clearly about Wendel is his exceedingly loving and accepting parents. Now of course, the ‘comically accepting old folks’ is a gay comedy cliché but in the mid-80’s this was quite revolutionary. Why did you decide to make Wendel’s sexuality such a non-issue with his parents?

There have always been parents who broke the mold and accepted their offspring’s gayness. Back around 1968, years before I was out to my mom, I once spent the night with an eighteen-year-old who insisted on taking me by the Dunkin Donuts outlet where his mother was a waitress the next morning. His mom wasn’t fazed in the least to meet the college kid who had just “tricked” with her son. Some parents just go with the flow that way.

“It’s hard to remember how unusual it was back in the 1970s, despite all the gains that were already in place from the Gay Liberation movement, to see cool gay people doing anything other than cruising, having sex, or being campy.”

Given Wendel’s ease with his sexuality at an early age, it seemed right that his mom and dad would be the sort who “got” the gay liberation movement – they being old-time ban-the-bomb-style “lefties” who had probably been hounded as Communists from time to time and knew a thing or two about “marching to one’s own drummer.” By contrast, Ollie came from the more conventionally uptight sort of family than many of us are more familiar with.

Do you ever find yourself looking back on your WENDEL strips and marveling at how much things have changed?

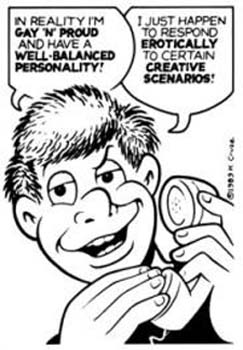

It’s a different world. Gay people still have a lot of battles to fight, but we’re far from invisible now. Creating GAY COMIX, the anthology underground comic I edited from 1980-84, meant breaking new ground in terms of giving myself and other LGBT cartoonists an opportunity to move beyond stereotypes and draw honest comics from their own individual perspectives and experience. The WENDEL series was an outgrowth of the visibility I gained from GAY COMIX, and other cartoonists have said they were also encouraged by both GAY COMIX and WENDEL to stretch themselves and draw openly about the gay world as they experienced it. It’s hard to remember how unusual it was back in the 1970s, despite all the gains that were already in place from the Gay Liberation movement, to see cool gay people doing anything other than cruising, having sex, or being campy.

Do you ever find yourself looking back and marveling at how little things have changed?

With the religious right now being sucked up to by two of the three branches of government and doing everything it can to take over the courts, it feels almost as scary to me now as it did under Ronald Reagan. Scarier, maybe, since the Bush crowd is so much better than the Reaganites ever were at making bigotry sound folksy. We need to remember [that] the visibility doesn’t solve the problem of homophobia. There was plenty of gay visibility, and a big liberationist movement to boot, in Germany before Hitler’s rise. We could still lose everything in America if we don’t pull together to reassert humanist values over cozy prejudices and the lust for money.

I’m not sure if it was that Reaganites were bad at masking their homophobia as much as they didn’t really have to mask it.

Even at its darkest and most serious, Wendel is a relentlessly cheerful and lighthearted comic strip. Was this intentional? And would the strip be as cheerful if it was written today?

Wendel himself is naturally good-hearted, which gives the WENDEL series as a whole a good-hearted core. Ollie, who becomes Wendel’s lover during the strip’s early arc, is older and more scarred by life. More like me, in other words! The strip never lost its cheerful tone in portraying its main cast of characters. They were likeable, imperfect people, like my friends in real life. But the strip gradually gained a darker side because of what was happening to gays and lesbians in the real world, which I always tried to mirror in the series.

You can see that darker aspect of the strip in episodes like the one where Sterno tells Farley a “scary” bedtime story that’s prompted by Reagan’s re-election in 1984. The kid ends up sleeping soundly while Sterno lies awake shivering in fear. There were fleeting references to AIDS in the early strips, but it took me a while to figure out how to portray an epidemic that was killing WENDEL’s readers one by one in a way that meshed with the strip’s comedic spirit. I had to avoid trivializing real-world tragedy and grief. I finally decided to shift the format of the strip further toward narrative continuity, de-emphasizing gags in favor of characterization and irony. The first time I drew an episode that ended without a punchline, I really felt liberated. The strip never stopped viewing life through a comic prism overall, but a lot more storytelling doors were opened once I broke free of the “punchline curse”!

The most memorable for me being the strip where Farley had to deal with his father and Wendel’s arrest at a gay rights march.

That episode was a landmark in its way, y’know. It was the first WENDEL strip that didn’t have a single gay character in it. Even in a gay-magazine series I resisted being hemmed in!

I recently loaned out my WENDEL collection to a friend who’s about ten years younger than me. He said that he liked the comic strip a lot, but didn’t think that it would work today. When I asked him why, he said because it was too earnest and the gays weren’t “bitchy” or clever enough. Do you think that’s true? Are gays now prisoners in a stereotype that we created ourselves?

I think the characters in WENDEL are plenty clever, but it’s true that bitchiness isn’t their style. That just reflects my own style and the style of most of the gay people I like, who are interesting and funny and impudent and ironic and political but definitely NOT bitchy. Bitchiness as a conversational staple is like refined sugar. It can give you a momentary rush but it’s got no nourishment value.

That said, I did worry while the strip was running that it was overloaded with earnestness. I tried to fight that tendency with satire and black comedy, and Ollie was much more given to a melancholy view of life than Wendel was. But Wendel was the title character, and there was no getting around the fact that his fundamental sweetness and idealism set the overriding tone for the strip, even when AIDS or gay bashing were the subjects at hand. When I later turned to STUCK RUBBER BABY, I had to admit that it was fun having a central character who could be as much of a jerk as Toland Polk could be. Toland’s character flaws made getting him into edgy situations easy.

When I loaned the same friend a copy of THE SWIMMER WITH A ROPE IN HIS TEETH he said that he was a little disappointed that it wasn’t a “gay” book. Do gay creators always have to make gay art?

Being gay is an important part of my life experience but other things in life are important to me, too. STUCK RUBBER BABY gave me the chance to wrestle with the way our psyches get bent by racism, even when our intentions are good, and to revisit the role that being a white Southerner during the Civil Rights era played in shaping me as a person. SWIMMER gave me a chance to comment about religion. Don’t forget, I’m a preacher’s kid, and my appreciation for and ambivalence about the religious influences from my childhood have been important threads in my art from day one. My first Barefootz story drawn for an underground comic was “Tussy Comes Back,” about a cockroach’s experience after death, and I satirized faith healers in the 1984 Dolly story “Oral Rubbers.” “Hell Isn’t All That Bad”, which appeared in an old Snarf, was another satirical riff on afterlife models. There are lots of things about life besides being gay that I feel passionate about, and it’s only natural that they’ll take turns being dominant in my art.

As it should. I only bring this up because so many gay readers seem to think that gay creators have a responsibility to create gay comics and editors and publishers seem to think gay creators only want to create gay comics. I’m reminded of the story Phil Jimenez tells about the DC editor offering to let him make Tempest gay when Phil did the mini-series. Why do you think so many people want to pigeonhole gay creators?

There’s a natural tendency to want artists to keep doing whatever they did that pleased us in the first place. When I was a kid I read an interview with Dr. Seuss in which he said he might write a musical comedy someday. I was one panicky ten-year-old, reading that. No, no! Don’t take time away from your picture books. More Horton the Elephant!! More Bartholomew Cubbins! It was important to me that a new Dr. Seuss picture book show up at the bookstore every single year! Without that, life would lose its meaning!

But artists have to find ways to be true to themselves, which usually means changing course every now and then so that new parts of themselves can get expressed. I’m gay, but I’m not just gay. A lot of what I have to say about the gay experience I’ve already said through WENDEL, STUCK RUBBER BABY, my GAY COMIX stories and my Village Voice strips from the ’80s. Covering old ground over and over would be pointless. The results would bore me and, believe me, they would bore you!

But that doesn’t mean I’m steering clear of gay topics in my work. When I find myself with something new and compelling to say about the gay experience, I’ll give priority to expressing it. And once in a while, when the opportunity presents itself, I’ll do something gay that’s of a lighter nature, like the strip I’m doing for Young Bottoms in Love.

“Humans are blessed with a capacity for great transcendence, and yet we seem determined to undermine every opportunity by exploiting our capacities in the shallowest and meanest ways possible.”

Besides, as I pointed out to my friend, given the protagonist’s constant working out and obsession with getting himself a swimmers build it’s entirely possible that he was gay.

Yeah, it was probably all the raunchy gay bars over in the Land of Evil and Woe that really got him swimming!

What was it about Jeanne Shaffer’s THE SWIMMER WITH A ROPE IN HIS TEETH fable that made you want to turn it into a graphic novel?

It’s a very simple fable that says something real about human behavior. It can be viewed as a comment on institutionalized religion, and it certainly is that. But it also comments on something larger. Humans are blessed with a capacity for great transcendence, and yet we seem determined to undermine every opportunity by exploiting our capacities in the shallowest and meanest ways possible. We build shallow rituals and institutions about vehicles for transcendence that life offers to us instead of using those vehicles to raise ourselves to more meaningful levels of existence. If SWIMMER had been nothing more than a Christ parable I wouldn’t have found it so intriguing, but I felt that Shaffer’s story had some real wisdom to offer that we would do well to reflect on, even if there’s not an ounce of religion in our bones. I knew the fable wasn’t a likely candidate for best-sellerdom, but I still thought it deserved to be available to the world instead of stuck in Jeanne Shaffer’s file cabinet. So I asked her permission to expand and illustrate it.

I don’t think of it as a “real” graphic novel, though. It uses almost none of the visual vocabulary of comics storytelling. It stands alone among my books, in its look and format, for better or worse.

Out of curiosity is there any talk of getting SWIMMER into schools? I can think of a few English teachers I had in school willing to kill to get an example of a fable this accessible into their curriculum.

Nobody has specifically raised that point with me. Maybe some teachers will latch onto it and feel as you do. At this point there’s not a lot I myself can do about it but mention it when opportunities present themselves. Maybe word-of-mouth from people who like it will keep it afloat.

STUCK RUBBER BABY was translated into what, four other languages? Is it surreal to have a book that you wrote translated into other languages? Do you ever wonder if the words have the same meaning when written in a language that you can’t understand yourself?

STUCK RUBBER BABY currently exists in German, French, and Italian, and a Spanish edition seems perpetually on the verge of coming out. A Spanish publisher, Dolmen, licensed the rights for a Spanish version years ago, and even though it keeps being delayed, they recently paid money to DC Comics to extend the license. So they’re presumably still serious about it. Meanwhile, Ediciones La Cupula has come out with a Spanish WENDEL, so I have a bit of a presence in Barcelona. Negotiations are also underway for a Dutch edition. DC Comics does all the foreign-language licensing for STUCK RUBBER BABY; I have no say in any of it, although money from overseas royalties does help chip away at the advance money that DC has to be repaid before I begin getting any new royalty STUCK RUBBER BABY checks. So I root for an STUCK RUBBER BABY translation in every country in the world, and it’ll be nice if most of them are well done. It’s all out of my control so I don’t worry about it.

How does it feel to have my stuff translated? I’m complimented, but I’m in no position to evaluate the translations since I don’t speak the languages. So far all of my translators have seemed to care about the job they were doing, and both Am Rande Des Himmels and Un Monde de difference, the German and French versions, won awards in their respective countries. So I choose to believe that everyone is doing a wonderful job.

What kind of feedback did you receive from foreign readers? So much of the book is steeped in American history and social issues that I always wondered how much of it would translate.

Once in a while I’ll get email from someone who has read one of the foreign-language versions, but for the most part whatever reactions it gets happens beyond my earshot. The same is true of WENDEL ALL TOGETHER, half of which hit Spain a year ago thanks to Ediciones La Cúpula and the second half of which is due to be published soon. I can say that STUCK RUBBER BABY was a hard sell for DC’s International Rights department for several years because no one knew how the Americana would communicate to French readers. But eventually Vertigo Graphic took the plunge and apparently it was well-received.

You’ve talked a lot about the four-year struggle that you went through to complete Stuck Rubber Baby, did you ever find yourself thinking about just giving up?

That truly was not an option. If I had given up I would have had to return my advance money, a large portion of which had already been spent by the time I realized how long the book was going to take to finish. Or I would have had to declare bankruptcy and stiff DC, after which my name would have been mud in the publishing world and nobody would ever have given me another book contract.

Besides all that, of course, I didn’t WANT to give up! Money issues aside, taking STUCK RUBBER BABY from concept to book was the most thrilling creative experience I have ever had. So once I realized that there was no good way out of a situation that remained rewarding even as it threw my personal finances into chaos, I just decided that I would have to plow ahead and get the thing done, however long it took and whatever the financial consequences. After it was finished I could survey the rubble and try to rebuild. Until then, I just wrote and drew and wrote and drew and wrote and drew until I finally got to page 210.

210 pages is a high page count for an original, over-sized graphic novel. Was it ever suggested or did you ever consider breaking the book up into chapters and publishing it as a mini series of some kind?

The idea was broached by others but I resisted. To do that, in my opinion, would have been short-sighted and would probably have doomed the project in the long run. After we talked all the angles through, others at DC accepted my argument.

The first few issues might have sold OK if STUCK RUBBER BABY had been serialized, but once the curiosity value surrounding the novelty wore off of a gay underground comix guy working for DC Comics, the book’s disturbing themes would almost certainly have led a lot of non-gay comics fans to peel off. The resulting drop-off in sales figures would have led DC to view the series as a failed venture. Look what happened to Owlhoots, the very interesting but never completed graphic novel that James Vance and John Garcia undertook some years ago at Kitchen Sink Press. Sales of the first few chapters weren’t considered strong enough so the title got cancelled. Who knows how nice a graphic novel Owlhoots might have been if Vance and Garcia had been able to deliver it to the world in a single bite?

I wanted readers to take the risk of committing themselves to a one-time purchase of STUCK RUBBER BABY. That way they could dive into the story and stay in until they finished. Having constant interruptions while readers waited for successive installments to come out would have dissipated the story’s urgency. At least, that’s the way I looked at it back in 1992, and I still think my argument was valid.

When making STUCK RUBBER BABY you did some extraordinary things to be able to afford to keep working on the book. How and when did you decide to start selling off pages of artwork before you had finished the book?

When it became apparent about six or seven months into the project that there was no way on God’s green earth that I could conceivably come anywhere near finishing the book before my advance money ran out, it was all I could do to keep from going into a total panic. My then-lover and now-husband Eddie suggested that we get together with some friends and brainstorm about how I could pull more money out of thin air so the book could be completed.

The idea of selling artwork from my book ahead of its publication came out of that brainstorming session. One of these friends was an experienced fundraiser for a non-profit social service agency. He helped me assemble the fundraising packet that we sent around to anybody any of us knew who had money to spare. We described the book, explained the financial crunch I was in, and asked them, in essence, to “sponsor” me based on my artistic track record and the substantive themes STUCK RUBBER BABY would be embodying. We had a letter from some cultural heavy-hitters attesting to the likely value of the book as gleaned from their reading of the early chapters. And Paul Levitz at DC Comics gave me permission to include in the packet a full-sized reproduction of one of the unpublished pages I had already finished by that time.

Several people, bless their hearts, pitched in and bought pages, which they couldn’t actually get their hands on until the book came out several years later. I’ll be forever grateful to these folks and their names are listed in the back of the book. I’m grateful to the folks who signed the endorsement letter, too. Without help from others I would have been in bankruptcy by 1994 and STUCK RUBBER BABY would probably never have been finished.

Beyond that fundraising effort, I borrowed on my insurance and ran up credit card debt to my nostrils. What finally put me over the top was a grant from the Stonewall Foundation that paid for the final six months of drawing. Finally knowing that I was really going to make it to the finish line was a huge relief. It was quite a creative adventure, and I never, never, NEVER want to find myself in that much of a financial pinch again!

As an artist or writer, when you look back on the entirety of your work is there anything that you wish you had done differently?

Nothing major. I have the usual number of small missteps to wince about, but most of the significant professional choices I made along the way were made for good reasons that still hold up. Life might have been simpler if I had had one of two slam-bang commercial hits along the way, but that’s about luck, not “doing things differently.” I’ve pretty much made the best art I’ve been able to make within the practical constraints of the cards life has dealt me. Frankly, that’s the only way I know to go about living life.

I certainly wouldn’t make a different decision about being out of the closet. All of my best work and most satisfying friendships have sprung directly from my decision to be honest about who I am.

You do a lot of non-comic work like advertising and graphic art. Is this “day job” just a way to finance your comic career or is it just as rewarding in its own way?

In a perfect world I suppose I would only spend time on “projects on the heart.” But given that I’ve got to make a living like everybody else, being an illustrator-for-hire from time to time has its satisfactions.

It’s usually an engrossing challenge to find a way to complement the spirit of an article’s text with my particular sense of humor, or to find a way to make some art director’s visual concept come to life interestingly. Even on those rare occasions when I pull in a buck purely as a graphic designer, with no drawings involved at all, it can be fun. It’s like making model airplanes. You get lost in it. It’s intrinsically gratifying when I can feel I tackled any project in an excellent way, as opposed to a mediocre way. And I usually pick up new skills along the way that I might never have learned if all I ever did was cartoon or make comics.

We’d like to thank Howard for his time spent in conducting this interview and for helping us bring Young Bottoms In Love to an end. For more info on Howard be sure to visit his site at Howard Cruse.com.

The interview as it appeared at PopImage may be read at the Internet Archive.

Howard Cruse’s website is preserved at the Internet Archive as well. This is link is to the site as it appeared on September 17th, 2019, two months before Howard’s death.