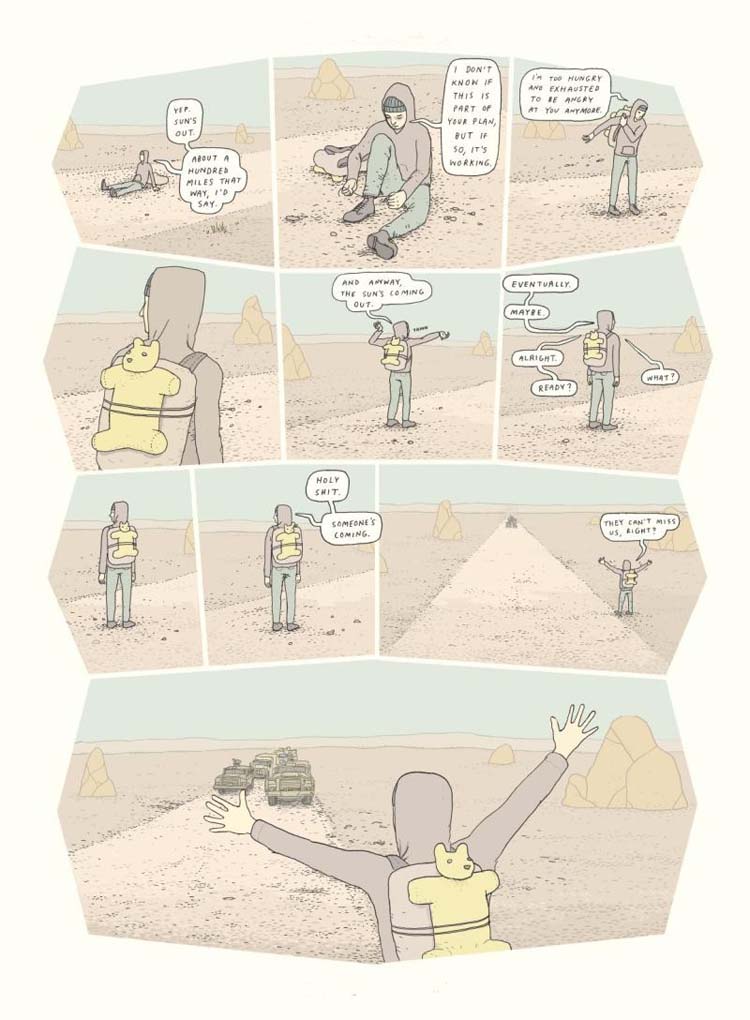

The mention of Prometheus is what drew my attention to Anders Nilsen’s recently released graphic novel Tongues. Between its covers Nilsen explores the story of Prometheus by bringing the eternally bound Titan into the present day as his beloved humans become a point of contention with other gods for the threats they pose to their fellow humans and the world. Intertwined with Prometheus’ plight is a young girl named Astrid who reluctantly sets off on adventure to safekeep a mysterious cube while a young man accompanied by teddy bear strapped to his backpack wanders a desert to discover he’s unwittingly caught between rival factions.

Fascinated by the story’s complexity and nuance in both words and visuals I found myself accepting an opportunity to interview Nilsen. I hope you will take time to read the result.

First, a mention that all the material from Tongues reproduced in this interview is copyright Anders Nilsen.

Joe Palmer: Hello Anders! How are you? It’s a pleasure to talk with you about your graphic novel Tongues. How has its reception been so far?

Anders Nilsen: I can’t complain. People seem super positive about the book, and reviewers seem to be reading it closely and getting what I’m trying to do. I’m very happy with the reception so far.

JP: There was also a book tour for Tongues which wrapped up recently and a couple of your stops also featured art shows. A book tour sounds like an incredible opportunity for meeting new people and old friends alike. Were there any serendipitous experiences or comedic mishaps for you while touring?

AN: I like the idea of a serendipitous mishap. Nothing so far quite fits that description, but in Chicago for several days in a row my wife and I had a pair of Canadian Geese hanging out on a rooftop below our hotel room, presumably taking a break from northerly spring migration. There do seem to sometimes be bird-themed incidents connected to tours for my bird-themed books. Or maybe they were just getting in some cross-border shopping before the tariffs took effect. But seeing distant friends has been a perk, for sure. I got to spend time with a dear friend in New York who I haven’t seen in person for the better part of a decade. And several events were set up as conversations with friends who are creative people of some sort or other, which was also great. Much more interesting than just me talking about the exact same thing night after night.

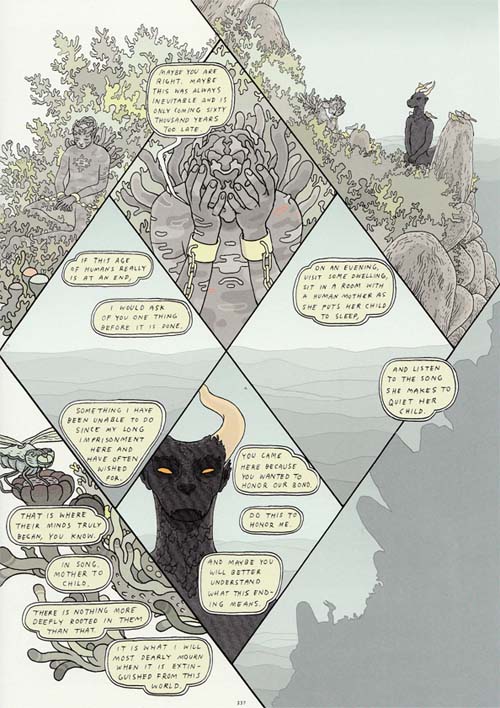

JP: Tongues is so densely packed with ideas that it’s a challenge to know how to start. At its core Tongues is about the Titan Prometheus who was punished by being chained to a rock and to have an eagle eat his liver every day for the rest of eternity after he gave fire to humans. Keeping this story confined to the past was something that didn’t interest you though. Would you please talk about how and why you expanded on the ancient Greek setting by bringing Prometheus and his eagle tormentor/friend into the present day? Perhaps a little about themes? Notions of time from human and divine perspectives? Climate crisis? The cult of power and the desperate lengths people will make to attain and remain in power?

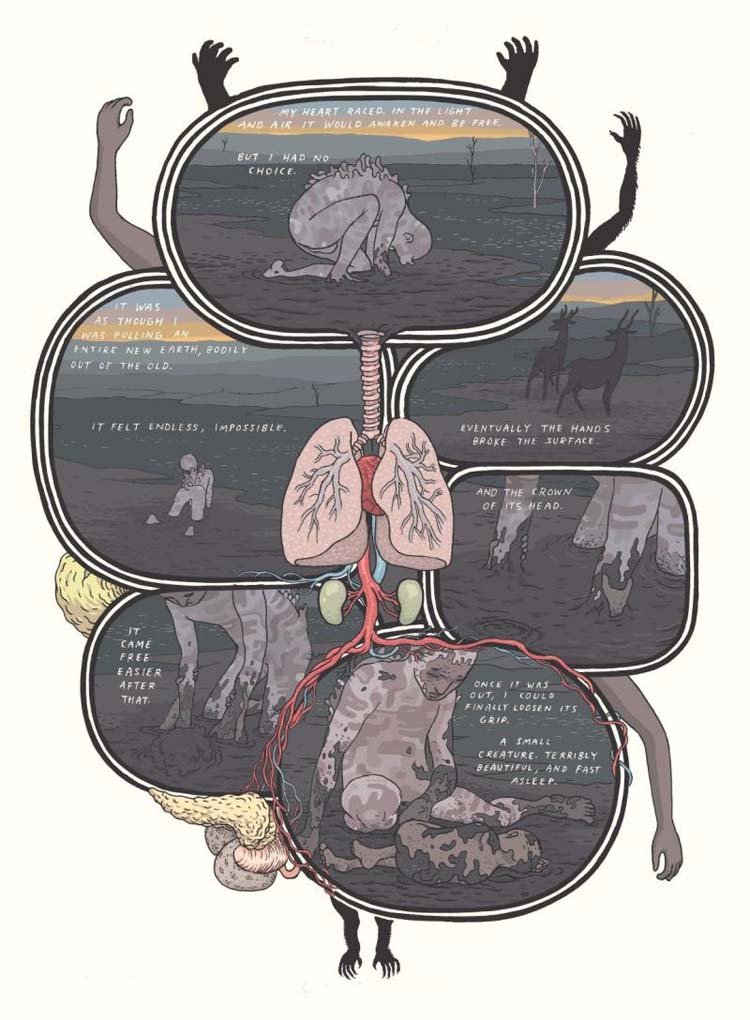

AN: Sure. The idea to bring the story into the present day comes from a couple of places. One is just that his punishment is traditionally understood as ‘eternal’, which, if you take that idea to its logical conclusion, implies that he’s still there. We are living in the unknowable future of the people writing those stories. But Prometheus is also the figure in Greek mythology credited as the creator of humanity. And so it seemed naturally interesting to think about, like, what would our creator make of his creation, now, in the present day if the last time he’d seen us we hadn’t even fully developed agriculture yet, say? We might have been interesting in certain ways in 40,000 BCE or 400 BCE at the height of Athenian civilization, but, for better and very likely for a lot worse, we are an extremely interesting species in 2025 CE. I wanted to explore that idea, and of course it leads to all the other things embedded in your question about climate and power and the strangeness of time.

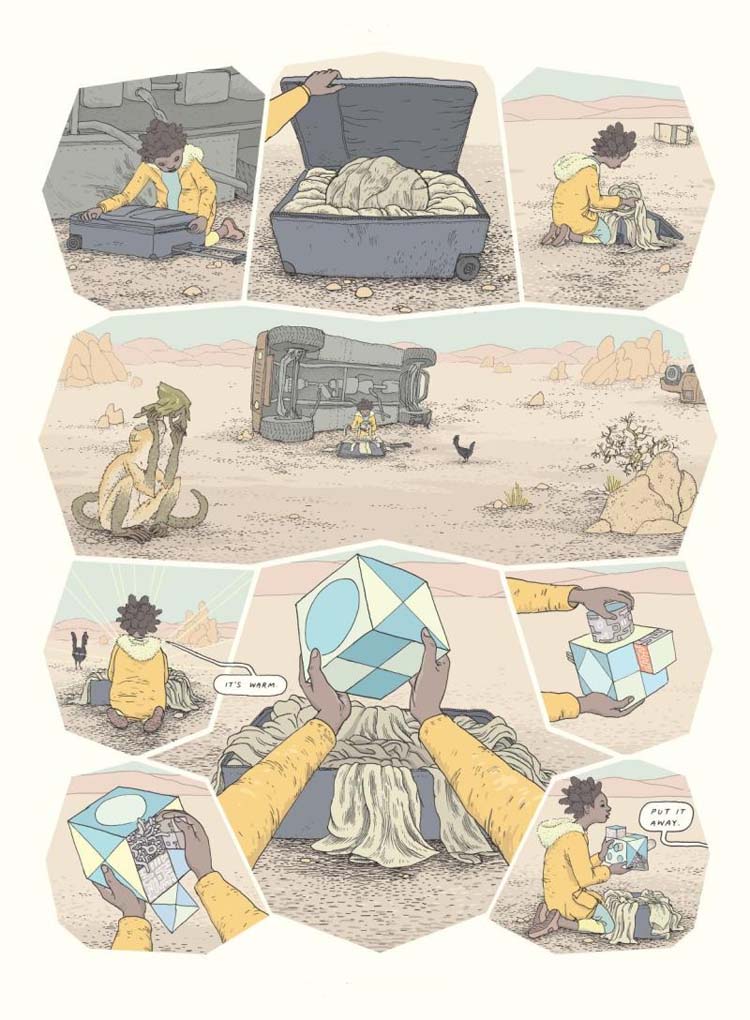

JP: It’s also the story of a young girl named Astrid who was orphaned as an infant who in turn is adopted and raised by another man. Astrid’s life drastically changes when she is caught up in truly fantastical circumstances. Did you set Astrid off on a hero’s journey?

AN: Sure, something like that I guess. I’m a sucker for a good hero’s journey just like anyone else. Or a sort of semi-traditional fantasy/quest narrative, maybe. But I’m also interested in playing with those tropes a little bit, poking at their inherent weirdnesses, or the funny expectations we have about them. At the start I wanted the book to be at least in part a kind of adventure story. You referenced some of the heavier thematic content above, but I wanted the book to be, like, a fun read, too. And so that’s one of Astrid’s jobs, is to carry that adventure piece.

JP: As much as this may be an adventure story, might it also read to be a bit of a love story? Not a romantic love but a paternal if unrequited love of a sort between Prometheus and humanity. It just occurred to me that this could be a story about love of a chosen family (humanity) over the love of a “family of birth” in that Prometheus is rejected by the other deities and you depicted a rather contentious relationship between Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus.

AN: That’s a lovely way of looking at it. And very applicable, yes. His relationship to humanity is also a bit fraught in a different way, but he’s definitely a bit caught between the two ‘families’. And I very much appreciate the idea of a paternal love story. The complex dynamics of fathers and their children is definitely a theme I seem to return to. I remember as a young person having the realization that not every love song is necessarily about romantic love. Not every “you” in a tune is a crush, or a lover. “You” could be a friend, or a parent or child. Or whatever god the singer might believe in. It suddenly made certain songs much richer for me. So yeah, I think it’s fair to say that the book is a kind of complicated love song about a god and his children. I might steal that from you. And the Greek myths, like any good soap opera are often driven by complicated paternity situations. So is the Christianity for that matter.

JP: You initially published Tongues in chapters starting back in 2017 if I’m not mistaken. How were you able to stay on track with the story as originally conceived and plotted or were there instances where a new insight or some change presented itself to tweak some aspect of a character or an event?

AN: In my memory now it was pretty clearly conceived from the start. But then when I look back at my early notes a lot of stuff is only very roughly sketched out at the beginning. It’s like you have to write the book if you want to figure out what it’s about.. And who exactly the characters are, what they care about, what their actual motivations are, what’s funny about them. So, like, how the prisoner actually feels about humanity… that’s changed since the start. Or at least taken shape differently than I expected. And I haven’t even written the final scene yet, partially because I’m waiting for a few of those quarters to fully drop before I’m ready to pull the lever. It’s important for me to let the book breath and not nail it down too solidly before I start.

JP: Two popular questions to ask creators, especially artists, in an interview are what was their introduction to comics and which creators have influenced their work. While those are valid questions, what makes me more curious is to ask about influences from or interests in other media that you may have.

AN: So a couple of important non-comics influences for me are biblical historians. Which might seem odd since I’m not a believer, or religious in any way. But Elaine Pagels book The Gnostic Gospels was pretty big for me in my teens and twenties, just kind of unlocking the idea that the construction of something as foundational as the bible is this super messy, human, contingent historical process full of agendas and eccentricities and weirdness. That opened a lot of doors for me. Following that line were a few books and works by Bart Ehrman, another biblical scholar. He drills down into the fine details of that history and exactly how historians parse an ancient text, but in such a way that it also becomes a kind of philosophical exploration of, like, how we construct knowledge in our own heads. So that’s fun.

I also love stuff like Tolkien and C.S. Lewis – The Narnia books but also his book Til We Have Faces, which is more for adults and a bit darker, even though I don’t think he means it to be. That one is also a retelling of a Greek myth, actually. In that case he’s playing with the story of Cupid and Psyche. And it’s just devastating. He tries to tack on a nice clean happy ending, which you kind of have to disregard, but if you end about two thirds in its one of the best novels ever written about love between siblings and about faith and doubt. And… complicated fathers. Because of course it is.

JP: On a related note, with elements of Greek and Roman mythologies being central to Tongues do you have any recommendations for curious people whose knowledge is more entry or intermediate levels?

AN: I would recommend Ingri and Edgar D’Aulaires’ book Greek Myths to anyone. It’s intended for middle grade kids I guess, but it’s one of the most beautifully illustrated books of any kind anywhere. And it’s a wonderfully evocative basic introduction to all the main stories in the pantheon. It’s a masterwork. Otherwise… I don’t know, I’m not that interested in artwork or literature that wears its connection to traditional mythology too much on its sleeve. I didn’t really mean to highlight that connection in Tongues, originally, it just started to feel silly to obscure it, and it was the easiest shorthand to describe what is otherwise a fairly complex story. The more an author makes the situations and characters their own, the better. If they become unrecognizable from their source, that’s preferable as far as I’m concerned. Drawing people in togas throwing lightning bolts was not at all interesting to me. There are different ancient versions of all these characters, that would likely have been unrecognizable to their respective authors. In some early versions of the Prometheus myth, he’s is just a trickster god, who’s playing a practical joke on Zeus. I don’t see myself as taking an old story and updating it, more participating in a long sequence of endless revisions and re-explorations of ideas. In that sense I would almost recommend, say Alan Moore’s Miracleman, or, like comics about Galactus and the Silver Surfer, because they are dealing in the same themes, even if they don’t name their characters Zeus and Athena or whatever. Although I will also say I loved Clash of the Titans as a kid, too, so togas can be fine once in a while in reasonable doses.

JP: Music figures into Tongues in a couple places. The first instance which comes to mind is an exchange between the character Violence [Kratos?] and the eagle [Aethon, Aetos Kaukasios] in the appropriately titled chapter “Human Music.” Violence is listening to a recording of a composition by Alfred Schnittke of a 12th century monk’s lamentations written at a time of great distress. The reference made me inquisitive so I searched for and listened to a Schnittke composition. Later in the story Prometheus implores his brother Epimetheus to listen to a mother sing her child to sleep as a way to understand their differences on a crucial matter. A lullaby and a choral being quite different from the other. I’m curious to know if listening to music is a part of your creative process and if so even more curious what was on your playlist while working on Tongues.

AN: Yeah, I do listen to music while I work, and it connects sometimes more than others. That Schnittke piece can be a little hard to find, but it’s pretty great – The Minnesang Choir. I’ve found it on Youtube before. There’s another specific piece I connect to the book, specifically to the scene with Astrid and her father at the mall. It’s a piece called Theory of Machines, by Ben Frost. Otherwise some of the music I probably spent a lot of time with while working on the book includes stuff like James Holden, Vessel, Greg Haines. And a band and artist that has meant a lot to me for a long time and has been a huge influence is Daniel Higgs and Lungfish. I’d probably think about a lot of artmaking differently if I’d never come across Lungfish.

I’m delighted that you noted the reference to lullabies. One book that was an influence was Finding Our Tongues by anthropologist Dean Falk. Falk is kind of reclaiming the story of the evolution of language, away from traditional male oriented anthropology which tended to want to say we evolved language to better hunt. Male anthropologists for a long time seemed to ascribe everything we do to the need for hunting and, like, warring for some reason. It’s almost a tic. Anyway Falk’s book argues that language started as a way for mothers to stay connected with their babies while hunting and gathering. Basically as a kind of auditory contact and reassurance. Lullabies, basically. The book is full of fascinating details supporting the theory, and that’s one of the ways it found its way into Tongues.

JP: You’ve talked before to some extent with Paste about your panel design and page structure. In that interview you mentioned that you quite understandably find drawing rectangles to be boring. In Dogs & Water panel borders are entirely non-existent. The opposite is true in Tongues where panels and page structure are prominent and as far from boring as I think has ever been accomplished in sequential storytelling. In fact, it’s fascinating from the first page and I wonder if you would talk about how you arrived at the choices you made and what the experience in designing pages and various sequences was like for you? Also, might there be symbolism in your choices of polygon shapes? I confess to trying to figure out if this might be the case but the information I found was inconclusive.

AN: Yeah, rectangles — they definitely have their place, but they are tedious to draw, which is to say, it’s not actually as straightforward as it seems to draw perfect rectangles with nice even little white gutters in between them all. For people who work that way, bless you, but I had to figure something else out. And along the way I discovered that the way panel borders are drawn can also have a lot of effect on the reader’s experience of the content of the story. My little experiment getting rid of them for Dogs and Water made that clear. So when I started Tongues I decided to make that a part of the project, exploring panel structure, and exploiting it in different ways. Of course not every page is precisely designed for a specific end, but in general the ‘normal’ pages in Tongues are intended to feel just a little like objects in and of themselves. maybe a bit like facets of a gem, or like planes in a folded or crumpled piece of paper. And that sense of folding or unfolding is meant to refer to the unfolding box that is at the heart of the story. So I guess it’s a small way to try and bring the reader into the story in a way, beyond just the traditional means of, like, good storytelling and pretty pictures.

JP: There’s another design aspect of Tongues and two other books that I’d like to ask you about. That being a book itself as an object. Rage of Poseidon piqued my attention because of the chapter devoted to Prometheus. The first thing I noticed and was astounded by when I looked at my library’s copy is its accordion style formatting. To my very limited knowledge this may be one of the few, perhaps only example of a mass produced graphic novel or art book. In your Poetry Is Useless you drew in sketch books and scanned or photographed its pages. Is that correct? And the pages are reproduced at various dimensions and often accompanied by drawings outside the scans. Images combined with images and combined with images again.

AN: Huh, yeah, I guess Rage of Poseidon might indeed be the first mass-produced accordion graphic novel. I hadn’t thought about it like that. I know Joe Sacco did an Accordion book that was a kind of story of the Battle of the Somme (I think) from World War I, so Rage isn’t the only one anymore, if it ever was. I have a lot of love for the content of Rage of Poseidon, but if I’m honest, I think it doesn’t do the form justice. I’ve continued to play with accordion books as a format for storytelling, and I think I’ve used it in much more interesting ways, since. Though only in limited editions. Actually the Tongues cube and Prometheus’ character design first show up in one of these: Box Landscape with Chase Scene, that I drew, originally around 2013 or so, I think, and made an edition of in 2019.

As for Poetry is Useless, yes, that book is basically just scans of my sketchbooks. The drawings reproduced outside the scanned pages are just bits I liked where the rest of the page maybe wasn’t that compelling. It’s made up of comics and drawings that are less planned, less carefully executed, more situational and improvisational than my other work. There’s a lot of me drawing on trains or out in the world at cafes and kind of responding to what’s around me. In a way it’s my favorite book. It’s the most playful and inventive work, and it feels in a way the most alive and uniquely ‘me’ somehow. It’s not the only way I want to work, I’m very much enjoying working on Tongues, too, even with all the necessary planning and labor, but if an asteroid came down and destroyed all my books, sparing only one title, I might hope it’d be Poetry is Useless. Probably. Maybe ask me again after Tongues Volume 2 is finished.

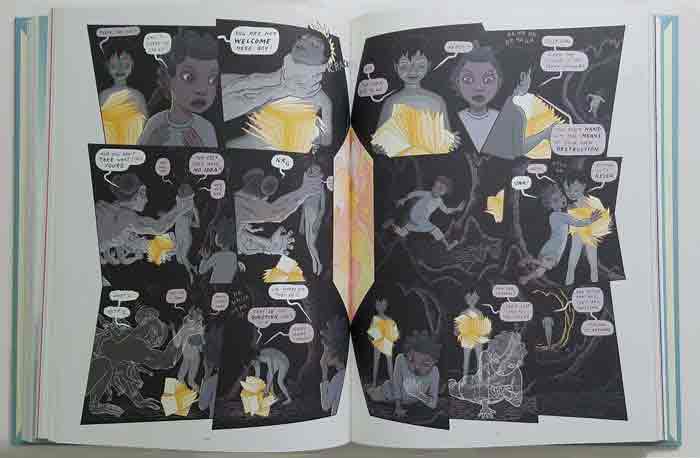

JP: Then there’s Tongues. The print version has a definite presence thanks to its page count and also its oversized dimensions. Aside from the book’s size are the front and back cover and spine designs and a couple other elements that I believe are exclusive to the print version. The sewn binding also allowed you as an artist to use the inside gutters of pages to your advantage. At the moment I’m looking at pages 222 and 223 and also 234 and 235. What considerations were on your mind when making these choices.

AN: Yeah, I’m very much interested in the possibilities created by the physical form of the book. I’m a cartoonist which is, of course, writing and drawing, but I also think of ‘the book’ as a medium of its own. Gutters, and bindings and folded paper, endpapers, spines. Playing with all that sort of thing in other book projects and especially in the sketchbooks that make up Poetry is Useless definitely fed into my approach with Tongues. Crossing the gutter the way I do in the two spreads you mention is an example. Normally you sort of ignore the gutter. Or it’s a kind of unfortunate weird curved vortex you don’t want to let any important information get too close to or it might get sucked out of the reader’s view. But you can think about it in other ways if you want. It’s like anything — there are habitual, traditional ways to look at it, and there are probably good reasons for many of them, but that doesn’t mean you can’t try other stuff, too.

JP: Another design element prominent in Tongues are various geometric shapes of varying complexity. These elements have appeared in some of your prior work such as Big Questions where they’re used both in stories and also the cover as is also the case with Tongues. The take on an almost logo aesthetic in Rage of Poseidon. They’re very intriguing in appearance and with my first exposure to them being in Tongues I’m thinking of them as a sort of sacred geometry. Would you talk about their usage and meaning in Tongues and your other work?

AN: When I first started getting serious about making comics it led me for the first time to look at the history of graphic design. And in particular things like the design of paper money and, weirdly, stock certificates. Both of which feature a lot of extremely intricate ornamentation, super complex, delicate linework. The reason for that kind of form is very simple – it made it more difficult to copy for counterfeiters. But I became interested in that kind of form for its own sake. Because of that history it carries with it a connotation of ‘value’ or ‘importance’. Which isn’t too far from ‘the sacred’. It’s also closely related to the aesthetics of, like, gothic cathedrals which were intended to be such complex, intricate collections of elements as to suggest the sort of infinite complexity and majesty and incomprehensibility of god. So yeah, like you say — sacred geometry. And Big Questions was, in small part, about things like that.

But I also just like the way abstract imagery can break up and give depth and texture to more readily readable kinds of images. Almost like a zen koan or something. Like, a comics page should create a comfortable rhythm and expectation for the reader of a certain kind of reading experience. And then you throw in something completely different and it forces their picture-interpreting brain to go to work on something less easy for it to crack. At which point, hopefully, maybe, something really interesting can start to happen.

JP: Now that Tongues is published do you have any ideas for your next project? More Tongues since this is volume one after all? If so will you take the same approach you did with this volume of publishing it in installments?

AN: Yeah, I’ll keep publishing the chapters as individual comics. It helps break up the long process for me, and does end up helping pay the rent between big books. I do have ideas for stuff post-Tongues. I actually have another sketchbook collection basically ready to go, but that work is, as I said close to my heart, so I’ll continue to do more stuff like that, very likely. And maybe some more essay-ish, non-fiction-y kinds of things. We’ll see. It’s not a question I’ll have to have a solid answer for for a few years, at least.

JP: We’re only a little more than four months into 2025 and so much of our society, government, and the perception of our country by fellow Americans and the world at large is in flux, to quite kindly understate the matter. How do you maintain your sanity? Do you have any sense yet of how creators are reacting to these absolutely insane tariffs that will affect graphic novels printed in China and South Korea?

AN: Yeah, It’ll definitely affect me in that way, as many of the self-published comics were printed in Asia. And prices for everything seem very likely to jump considerably. And a lot of smarter people than me see a recession coming up quick. So I think printing costs might be the least of it. I really have no idea. Traditionally the ruling class in this country doesn’t let a president get too far ahead of themselves. But they’ve given this one a lot of rope, and he seems intent on hanging everyone with it. It really does look like it might be the first time members of the elite are actually more scared of the president than the other way around. So we’re in new territory.

As for staying sane… I go for walks in the park, how’s that for an answer? I was actually in bed sick for the last few days and just this morning finally felt well enough to get up and walk outside for the first time. And it felt kind of glorious. It probably sounds silly, but the birds singing and the light filtering through the trees, the breeze on my face… it made a very real difference for me. Tariffs will happen and it will throw the world into chaos and then someday they’ll go away and something else will happen in the news and those trees and those birds and that breeze will still be there. And so I try very hard to appreciate that when I can. I live near Griffith Park in Los Angeles, which is a treasure.

I also just organized a fundraiser for Doctors Without Borders and the ACLU, too, in conjunction with my book tour. And raised a little over $5000, which felt a lot better than doomscrolling. Which I was also doing. But still.

JP: Ending this interview is difficult for me. I fear I’ve asked a succession of insipid questions which will have bored you.

AN: Not at all. Hearing people’s thoughts and interpretations of the book is often super productive for me, this interview included. When you put a work out into the world, in a way you are giving up control over it. You just can’t be sure what people will see in it, if anything at all. You just try and create something that speaks to you and assume that if so, it will also speak to a larger audience. But it might not say exactly the same thing to them that it says to you. If you’re lucky what comes back is stuff you couldn’t have guessed that deepens your own relationship to the work, even if only in small ways. Your questions were great.

JP: At the same time there are so many more topics and ideas vying to be asked that will only prolong sending this list to you. You’ve given me — well, readers — a story that can be returned to many times to discover more nuance. Even small details such as Astrid’s adoptive father’s name Alhadi adds meaning. Thank you so much for your time and patience, Anders.

AN: Very happy to take the time.

Tongues is available for purchase now. Please support your local bookstore and comic shop. A copy of Tongues may be bought from Bookshop. Bookshop can also help you find an indy bookstore near you.

Barnes & Noble has copies too.

If all else fails or you prefer, you can find copies at Amazon.

Please check this page if you’re looking for other retailers.